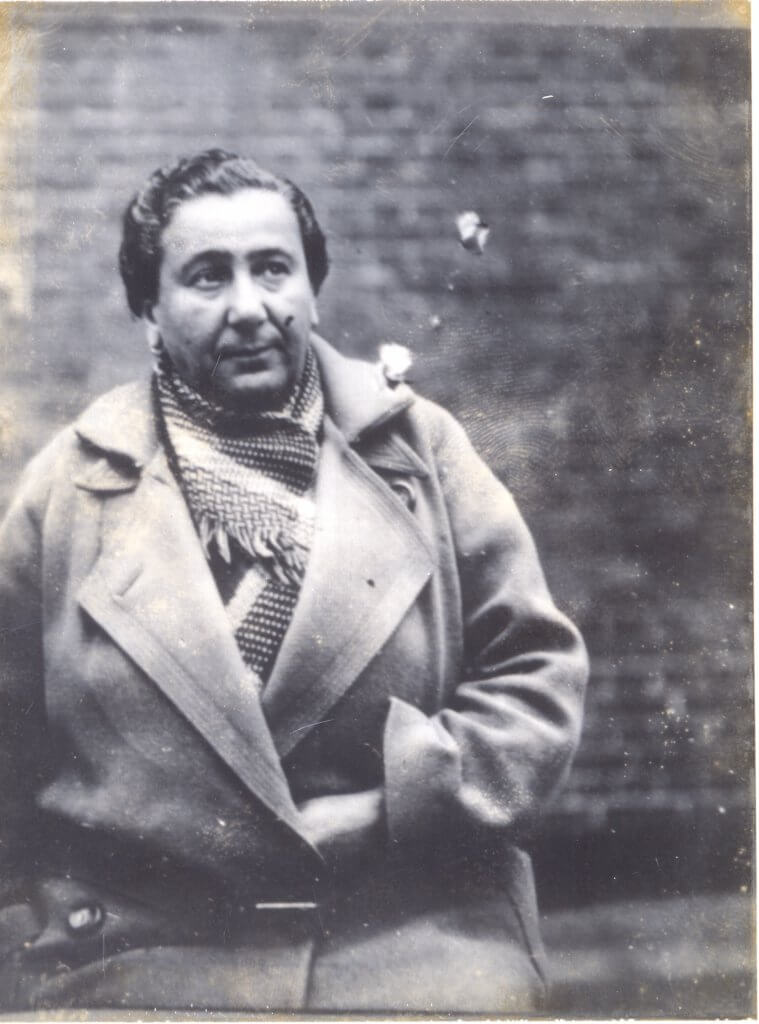

Elsa Conrad (1887-1963)

40 - Club „Monbijou des Westens“ / „Mali & Igel“, 1927-1933

Lutherstr. 2 (previously 16), Berlin-Schöneberg

Elsa Conrad, known as “Igel” (German for Hedgehog), was the successful owner of the Mali und Igel club and shaped lesbian nightlife in the late 1920s with her legendary women’s club Monbijou des Westens. Because she spoke disparagingly about the Nazi regime, loved women, and was half-Jewish, she suffered Nazi persecution, first in prison and then in the Moringen concentration camp. She was only able to escape the ordeal of the camp on condition that she leave the country. She fled to Nairobi and returned to Germany years later, impoverished.

read more

(this text can also be heard in the audio clip)

Elsa Conrad was born in Berlin as Elsa Rosenberg on May 9, 1887. After completing a commercial apprenticeship, she married waiter Wilhelm Conrad in 1910—this was presumably a sham marriage to a man who was also homosexual, and they divorced in 1931.

In 1925, Elsa Conrad, also known as “Igel” (Hedgehog), ran a wine bar with a gramophone for a lesbian clientele on Olivaer Platz in Charlottenburg. Around 1927, she opened “Mali und Igel” at Lutherstraße 16 (now number 2), which she ran together with her friend Amalie Rothaug, known as “Mali.” This was where the legendary women’s club “Monbijou des Westens” met. The club developed into one of the most exclusive meeting places for women who loved women.

The women’s association “Monbijou des Westens” had around 600 members and was a strictly closed society. In her 1928 city guide “Berlins lesbische Frauen” (Berlin’s Lesbian Women), Ruth Margarete Roellig described the club as “a gathering place for the elite of the intellectual world, film stars, singers, actresses, and women working in the arts and sciences in general.” It was “by far the most interesting association of lesbian women in Berlin. […] a strictly closed society that can only be entered through introduction or recommendation. The club is located in the elegant west of Berlin on the corner of the quiet Wormser and Luther streets, and is skilfully run by two intelligent friends, Mali and Igel, one a consummate garçon type, refined and self-aware, the other more of a high-spirited gamin.” The two operators are described very differently. Igel as “strong, a little plump, short hair, hands always in her pockets, boyish,” while Mali was “the opposite in appearance.” Hilde Radusch remembers Mali as “a dream of a woman. Racial, brunette, in loose, soft dresses and with that certain something that you can’t resist.”

Prominent guests included Marlene Dietrich and Gertrude Sandmann. Sandmann recalled, “People danced, flirted, talked to each other.” The club was so well known through word of mouth that advertising was unnecessary. Men were only allowed in on rare occasions. The club’s annual balls and costume parties, which also took place in the neighboring Scala and were reported on by the Berlin press, attracted a great deal of attention.

The rise to power of the National Socialists brought an abrupt end to the flourishing homosexual subculture. A decree issued by Hermann Göring in February 1933 to “combat flophouses and homosexual establishments” led to the closure of the “Mali und Igel,” which was enforced by the police in early March 1933.

Since Elsa Conrad did not hide her critical attitude toward National Socialism, she was arrested on October 5, 1935, as a result of a denunciation by her subtenant. The complaint included several allegations: Conrad had concealed both her ancestry, which was considered “non-Aryan” according to Nazi racial categories, and her lesbian orientation. In addition, she was charged with making statements critical of the regime. She was said to have stated that listening to the Horst Wessel song made her feel sick, and she had alleged that Hitler and Rudolf Hess had a homosexual relationship.

On December 18, 1935, the court sentenced Elsa Conrad to one year and three months in prison for “insulting the Reich government” under the Malicious Acts Act of 1934. She spent this time in the Barnim and Kantstraße women’s prisons in Berlin. After her release on January 4, 1937, she was only free for one day before being sent to the Moringen concentration camp. She was placed in protective custody in the concentration camp because of her criticism of the Nazi regime, her prominent role as a lesbian activist, and her classification as “half-Jewish.” The protective custody order specifically emphasized that Conrad was “lesbian-inclined.” The detention by means of “protective custody” took place without a trial and for an indefinite period.

Her release from the concentration camp was only possible on condition that Elsa Conrad leave Germany permanently. Her former long-term partner, Bertha Stenzel, worked tirelessly to obtain the necessary identity documents and travel papers. Nevertheless, Conrad was confronted with a multitude of bureaucratic hurdles. It was not until February 1938—after she had already lost a paid ship passage due to the delays—that she was released from the Moringen concentration camp, severely weakened by illness.

On November 12, 1938, Elsa Conrad managed to flee to Kenya. From 1943 onwards, she lived in Nairobi, where she ran a milk bar and kept her head above water by working as a nanny and saleswoman. In Nairobi, she met Stefanie Zweig’s family, whom Elsa immortalized in her 1995 autobiographical novel “Nowhere in Africa.”

Seriously ill and penniless, Elsa Conrad returned to Germany in 1961 and died there on February 19, 1963, in Hanau. Her long-time partner Amalie Rothaug had emigrated to the USA in 1936 due to her Jewish heritage, received American citizenship in 1950, and died in Florida in 1984 at the age of 94.

In Berlin, an attempt was made in 2021 to name a small square at Apostel-Paulus-Straße/Salzburger Straße “Mali-und-Igel-Platz” (Mali and Hedgehog Square), but so far without success. Elsa Conrad is considered a rare documented case of a woman who was arrested specifically because of her homosexuality and deported to a concentration camp—a fate that is representative of the systematic persecution of sexual minorities under National Socialism.

Other places with Elsa Conrad:

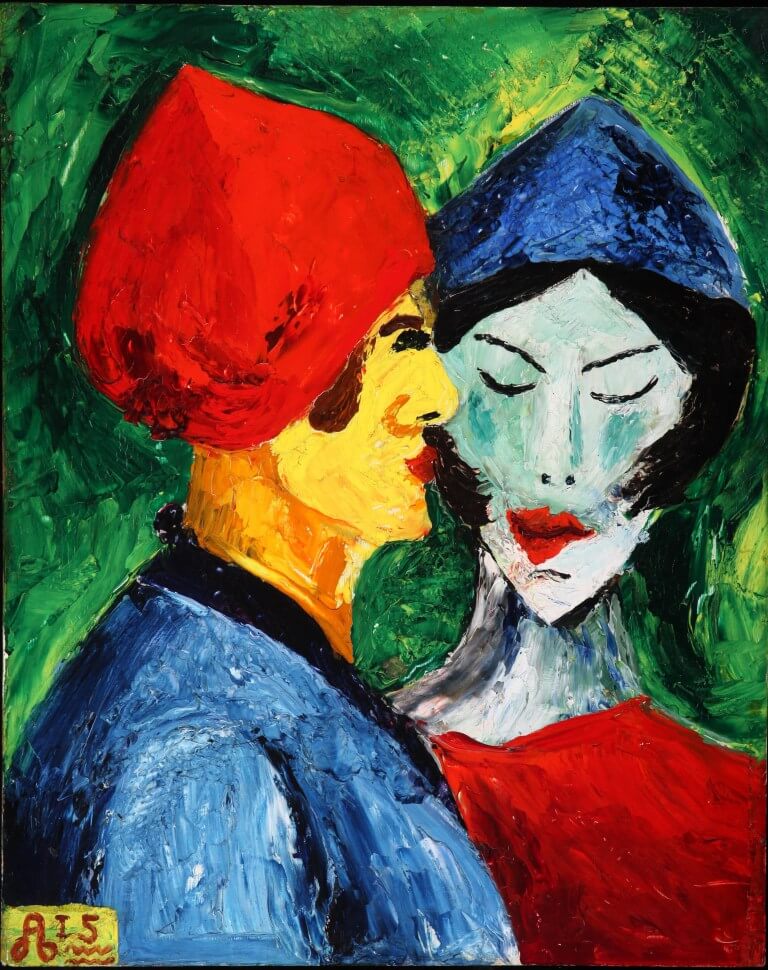

Image gallery Elsa Conrad

Further places & audio contributions

Further audio contributions nearby:

Related links & sources:

- [in German] Article „The most interesting association of lesbian women in Berlin: Club owner Elsa Conrad (1887-1963)“ by Claudia Schoppmann, in: „Spurensuche im Regenbogenkiez: Historische Orte und schillernde Persönlichkeiten“, MANEO-Kiezgeschichte Bd. 2 (Berlin: Maneo, 2018): pages 102-119.

- [in German] Article „Historische Orte und schillernde Persönlichkeiten im Schöneberger Regenbogenkiez. Vom Dorian Gray zum Eldorado“, by Andreas Pretzel, Maneo-Kiezgeschichte Band 1, page 111, Berlin, 2012.

- [in German] Article „Vier Porträts“ u.a. „Elsa Conrad“ by Claudia Schoppmann

- [in German] Online Article „Elsa Conrad“ by the Moringen Concentration Camp Memorial

Note on terminology:

Some of the terms used in the texts are used as they were common at the time of the queer heroes, such as the word “transvestite”, which was chosen as a self-designation by some people. Today, we would express this in a much more differentiated way, including as trans*, crossdresser, draq king, draq queen, gender-nonconforming or non-binary. Where possible, the terms that the person (presumably) chose for themselves are used, but in some cases we do not know how the people described themselves or how they would describe themselves using today’s vocabulary.

In addition, the word “queer” is also used, which did not even exist at the time of most of the queer heroes described. Nevertheless, today it is the most appropriate word to describe inclusively all those who do not correspond to the heterosexual cis majority.

A project by Rafael Nasemann affiliated to the Magnus-Hirschfeld-Gesellschaft e.V., Berlin.

Funded by the Hannchen-Mehrzweck-Stiftung – Stiftung für queere Bewegungen

The map on this site was created using the WP Go Maps Plugin https://wpgmaps.com, thanks for the a free licence

© 2026 – Rafael Nasemann, all rights reserved