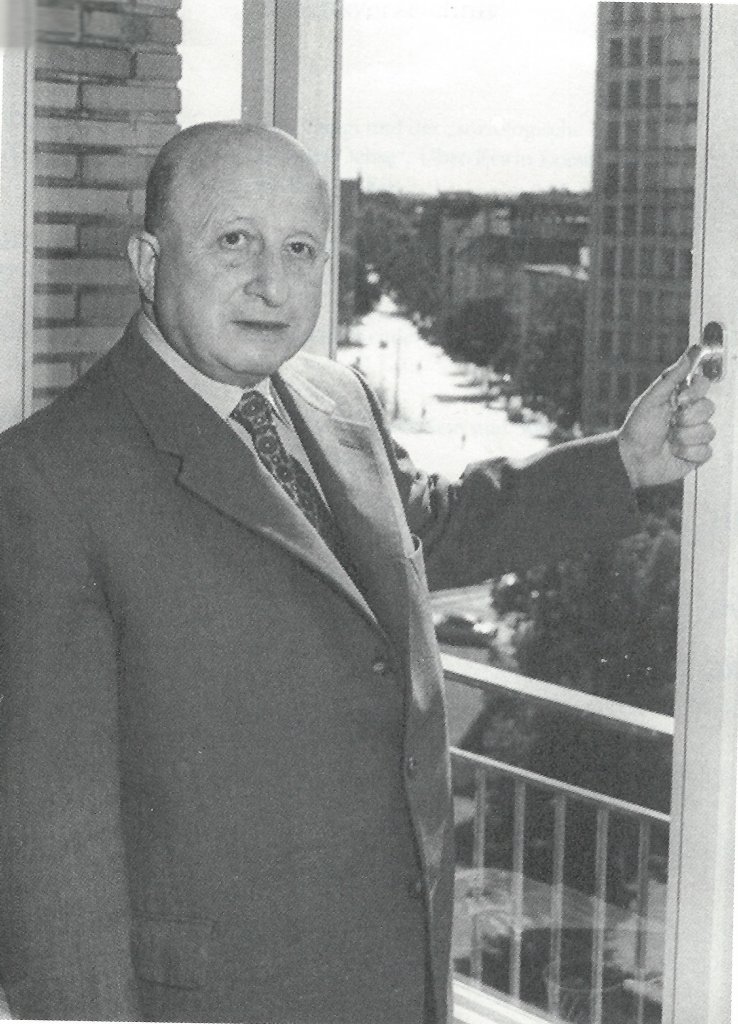

Kurt Hiller (1885-1972)

62 - Kurt Hiller memorial plaque at the place of residence 1921-1934

Hähnelstr. 9, Berlin-Friedenau

Kurt Hiller was a writer and one of the most important, but today largely forgotten, pioneers for the rights of homosexual people in German-speaking countries. As a gay Jew, socialist, and pacifist, he was an outsider and the target of discrimination throughout his life. During the Nazi era, he was interned and abused in the Oranienburg concentration camp. He was one of the most uncompromising voices for emancipation and self-determination. His work, especially in the fight against §175, made him a key figure in the early gay rights movement.

read more

(this text can also be heard in the audio clip)

Born into a wealthy Jewish family at Wilhelmstrasse 12 in Berlin, Hiller excelled as a student at the Askanisches Gymnasium and went on to study law and philosophy. At the age of 23, in his dissertation “Das Recht über sich selbst” (The Right to Self-Determination, 1908), he was one of the first to demand the right to self-determination for all people – including in the sexual sphere – and spoke out clearly against §175, which criminalized male homosexuality. Hiller was convinced early on that sexual orientation was innate and that social repression caused psychological problems, not homosexuality itself.

In 1908, Hiller became a member of the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee (WhK), founded by Magnus Hirschfeld, and rose to become its second chairman in the 1920s. In addition to his legal and political work, he was a prominent writer and publicist who wrote for the Weltbühne, among others, and was considered one of the most important theorists of literary expressionism. In his book “§175. Die Schmach des Jahrhunderts” (Paragraph 175: The Shame of the Century), published in 1922, Hiller presented an open and scientifically based indictment of the criminalization of homosexual men that was unprecedented at the time. He argued that homosexuality was a natural phenomenon and that social exclusion led to suffering and psychological problems. He pointed out the social conditions gay men lived in back then. He said mental health issues in this group weren’t a trait, but a result of social pressure—pressure that society created and then mocked. These ideas are still relevant today.

Hiller didn’t just criticize mainstream society, but also gay people themselves: he said they shouldn’t beg for acceptance, but confidently demand their rights. “You have to demand, not beg!” he wrote, anticipating the combative spirit of the later gay movement and today’s self-confident Pride movement.

In 1926, he founded the “Group of Revolutionary Pacifists,” which also included women’s rights activist Helene Stöcker and writers Klaus Mann and Kurt Tucholsky. In 1929, the pacifist Hiller called for a ban on wars of aggression to be written into the constitution. Since the KPD did not support the ruling SPD in this legislative project, it failed – and Hitler’s later war of aggression was therefore not unconstitutional. Hiller’s demand was finally implemented in the Basic Constitutional Law of the Federal Republic of Germany.

In 1928, Hiller called for a reform of criminal law, particularly with regard to Paragraph 175. The efforts of Hiller and his colleagues in the WhK finally bore fruit: the Criminal Law Committee of the German Reichstag decided to no longer criminalize homosexuality in the planned new penal code. However, due to the economic crisis and the emergency cabinets, a vote in the Reichstag never took place.

His romantic relationships, which he described in his autobiography, apparently remained limited to mere hand-holding. Not even a kiss was granted to his lover. His hidden sex life took place in the Tiergarten – encounters with sex workers that ultimately led to blackmail.

When the National Socialists came to power, Hiller was persecuted on three counts: as a Jew, a socialist, and a homosexual. In March 1933, the SS stole and destroyed many documents and letters from his apartment at Hähnelstraße 9, including correspondence from Sigmund Freud, Heinrich Mann, Thomas Mann, and Albert Einstein. From June 1933 onwards, he was arrested several times and severely mistreated in the early concentration camps. He was first held in the Columbia-Haus police prison, later the Columbia concentration camp, then in the Brandenburg and Oranienburg concentration camps. Thanks to the persistent efforts of his lawyer, Dr. Flato, and the intervention of Rudolf Hess, he was released from the Oranienburg concentration camp in April 1934. Hess, who was Hitler’s deputy, owed a favor to an officer who had given him protection during Hitler’s 1923 coup attempt. This officer now demanded a favor in return, which led to Hiller’s release. Hiller first fled to Prague, then to London, where he continued to publish and campaign for gay rights. From exile, he was one of the few who drew attention to the situation of homosexuals in Nazi Germany. He also published articles about his experiences in German concentration camps.

After the war, Hiller returned to Germany in 1955, lived in Hamburg, and attempted to reestablish the WhK—but failed due to the social conditions of the young Federal Republic. He remained active as a publicist, publishing in Vorwärts, Konkret, and the Swiss magazine Der Kreis, among others, and continued to campaign for the rights of sexual minorities. Little is known about his private life during this period; he had a close relationship with Walter Detlef Schultz, the program director of NDR.

Kurt Hiller died on October 1, 1972, in Hamburg. The urn containing his ashes was buried in the grave of his friend Walter Detlef Schultz.

Hiller’s importance to the gay movement was long underestimated. In 1990, a Berlin memorial plaque was installed at his former residence at Hähnelstraße 9. Since the turn of the millennium, the Kurt Hiller Society has been working to make his legacy visible. In 2000, a park in Berlin-Schöneberg was renamed Kurt-Hiller-Park on the initiative of the Berlin Lesbian and Gay Association (LSVD) in memory of Hiller as a co-founder of the homosexual civil rights movement. In 2021, a memorial plaque was unveiled there.

Image gallery Kurt Hiller

Further places & audio contributions

Further audio contributions nearby:

Related links & sources:

- Online article (in German) „Fighting for gay rights: ‘You have to demand, not beg!’“ by Michael Freckmann, 2022

- Audio clip (in German) “21 years in exile in England – Interview with Kurt Hiller” NDR Retro – From Culture · August 17, 1955

- Online article (in German) “Kurt Hiller – Lawyer and Writer” by Alexander Zinn, 2017

- Online article and biography (in German) by the Kurt Hiller Society

Note on terminology:

Some of the terms used in the texts are used as they were common at the time of the queer heroes, such as the word “transvestite”, which was chosen as a self-designation by some people. Today, we would express this in a much more differentiated way, including as trans*, crossdresser, draq king, draq queen, gender-nonconforming or non-binary. Where possible, the terms that the person (presumably) chose for themselves are used, but in some cases we do not know how the people described themselves or how they would describe themselves using today’s vocabulary.

In addition, the word “queer” is also used, which did not even exist at the time of most of the queer heroes described. Nevertheless, today it is the most appropriate word to describe inclusively all those who do not correspond to the heterosexual cis majority.

A project by Rafael Nasemann affiliated to the Magnus-Hirschfeld-Gesellschaft e.V., Berlin.

Funded by the Hannchen-Mehrzweck-Stiftung – Stiftung für queere Bewegungen

The map on this site was created using the WP Go Maps Plugin https://wpgmaps.com, thanks for the a free licence

© 2025 – Rafael Nasemann, all rights reserved